Macarena Rojas Osterling

‘Draughtswoman’

Curated by Jenn Ellis

Exhibition March 7 – 13, 2024. Shreeji Newsagents, 6 Chiltern St, London W1U 7PT

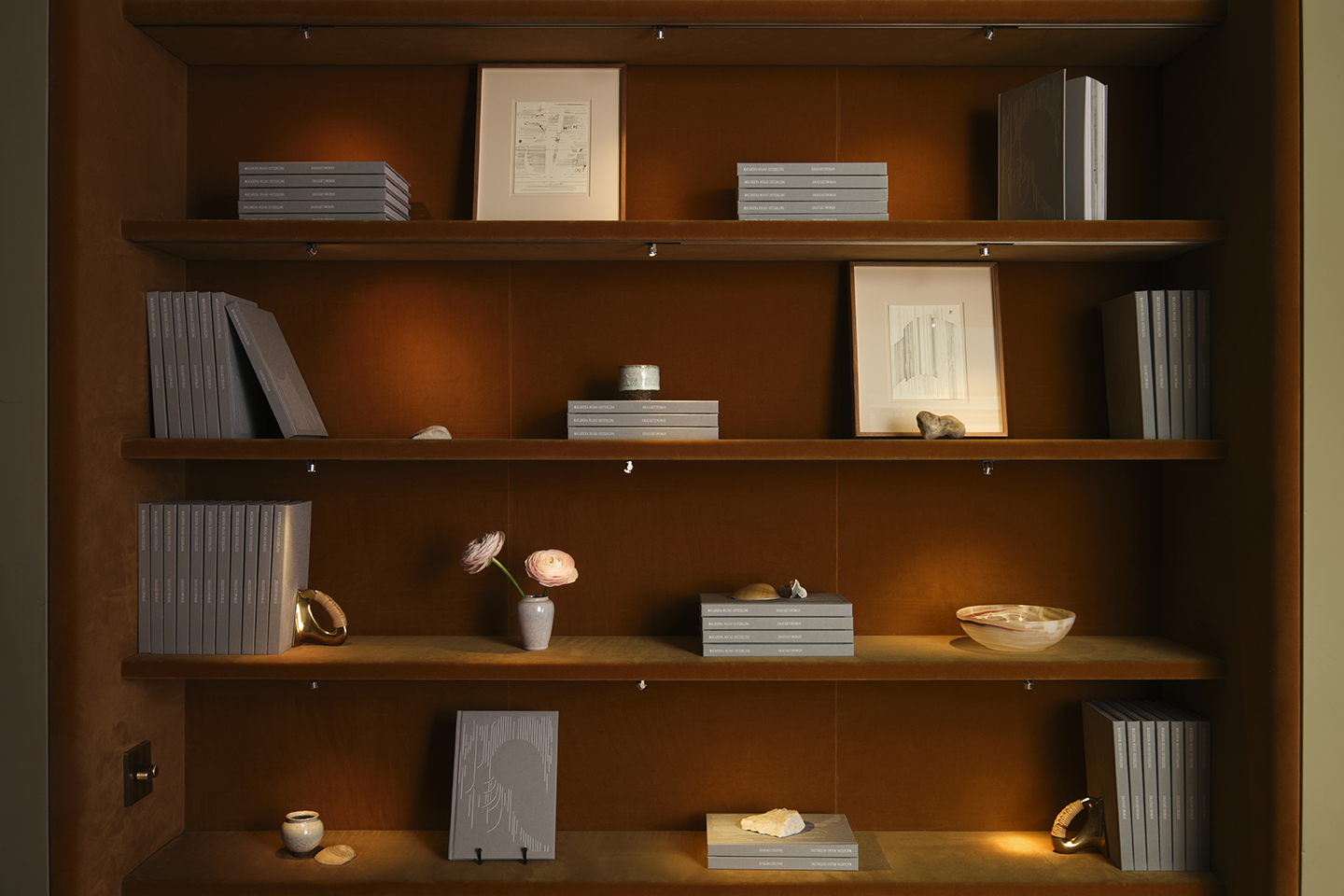

Macarena Rojas Osterling, Shreeji Newsagents, 2024. Photography by Ollie Tomlinson

“There is something extremely raw, close and honest about our attempts on paper. Not only does paper’s materiality have infinite alternatives, but so does its scale and the malleability of its presence.” – Jenn Ellis

Macarena Rojas Osterling is a master Draughtswoman. From pen to pencil she navigates the mediums, driving their capacities while breaking away from their traditions. Too neat? She strays. Too sporadic? She brings it back. Apsara Studio is delighted to share Rojas Osterling’s solo exhibition and book launch at Shreeji Newsagents in Marylebone, London. Curated by Jenn Ellis and set in Shreeji’s delicately-appointed near domestic space, a series of new works on paper alongside a selection produced between 2020 and 2023 are displayed. Speaking to the intimacy of the works, we’re invited to explore their deliberateness, balanced with vivacity and movement, which seem to span multiple worlds – that of architectural renders, musical compositions, celestial formations and care-free doodles. The exhibition coincides with the book launch of “Draughtswoman” (designed by Peru-based design studio Estudio Blanco), a comprehensive exploration of Rojas Osterling’s artistic journey, intertwining her drawings and archival materials with texts by curator Jenn Ellis, composer Alex Mills and architect Max Moya.

Individually and carefully placed in the space, Rojas Osterling’s works open crucially multilingual and pluralistic conversations. A huge component of their presence, distinctness and beauty is that they feel like a sum of all parts: in a past life she studied architecture in Lima then photography in New York; she has collaborated with her husband who is a musician; she now lives in London yet grew up in Peru; she is a mother; she is an Artist. In their variance and openness to possibilities, Macarenas’ works seem to see you, perhaps not in the way you’d seek to appear, but rather the way you are, in all your complexity and difference. Their ‘mirror’ quality is crucially not a confronting or castigating one but rather a welcoming and playful one. Their characters are not of the colder climate where we are encountering them but rather the warmer lands of her roots where there is an immediate human warmth and a ‘quick to share’.

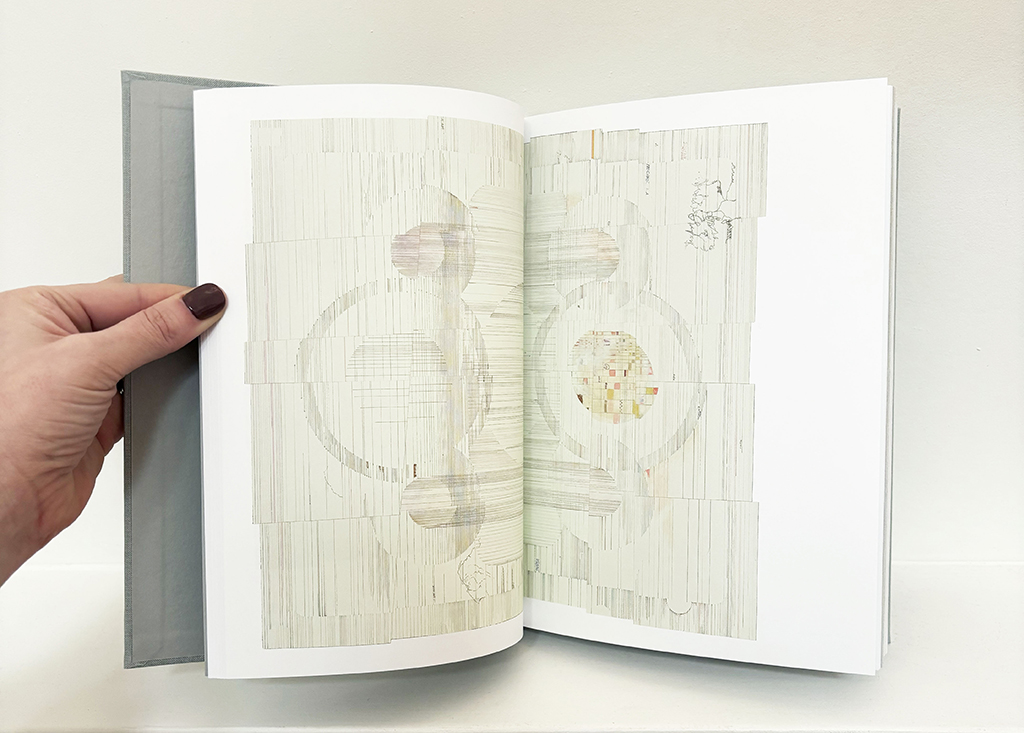

Rather than being one thing, Osterling’s work is brimming with multiplicity and references; it’s an interiority exposed, an expression of herself, of her life, the big and the banal that makes her, her. In their openness and articulations of the quotidian, Osterling’s drawings place her in a unique space of past to present figures who have defined and refined artist drawings. Consider the work ‘Madre solo hay una’ (2022), for example. Its emphasis on following a line draws analogies to the likes of Sol LeWitt. However, it is not bound by control or theoretical thought; a cerebral agenda and set of prescribed rules does not govern the hand and the wrist. Then, in its patterning and intricate trace-like weaving on paper, it might feel more akin to the works of Lygia Pape or Anni Albers. Yet, the work is not strictly geometrically-led: it has little scribbles, notes, annotations and some more visible lines such as ‘finding Lilito’. In its humour and play, the work in spirit feels more akin to Kandinsky or even Miró, where there is a sense of movement, dance, song – of whimsy. Yet, the works are not completely of their world either. This is a referential conundrum one encounters when reading, feeling and seeing the rest of Osterling’s drawings, such as ‘Johny Johny yes papa’ (2020) and ‘Louis’ (2020). Perhaps this is because Osterling’s drawings aren’t treatises, concepts or studies: they tell a story, and a very real one. Blending nods to Minimalism and Concretism with touches of humanity, they inhabit and belong to the realms of consciousness.

Ultimately, Osterling’s work is that of an observer. An artist who observes not only with her eyes but also her hands, ears and heart; a visceral training perhaps only a mother or parent can receive. Through her drawings, Osterling articulates with dexterity and soul a sense of how we live and who we are. She is able to capture an instant, as it is and was, and appreciate it, hold it for that moment in time, for us to revel in it and feel. Of multiple places, homes and phases, Osterling shares with us, with utmost honesty, a relatable diary of tension, vulnerability, control and happenstance; the little nothings that cumulatively add up to our special something.

Text by Jenn Ellis

Macarena Rojas Osterling Interviewed by APSARA

‘I love composing spaces, framing spaces, lighting spaces… I think my drawings definitely come as a response to finding control and balance, to keep things in place.’

Tell us about your Peruvian roots, your migration to the UK, and the conditions in which you became an artist, in particular your relationship to the medium of drawing.

I was born and raised in Peru during a very problematic decade in the history of the country. Hyperinflation was skyrocketing and “The Shining Path” – a far left guerrilla organisation – was constantly exploding bombs in Lima. I like to call them terrorists, but some people wouldn’t agree. My identity is that of a post colonial hybrid because although my ancestors have been in Lima since the Spanish arrived back in the 16th century, the country has so many wounds that you are still somehow perceived as a foreign European. I am a mix of the indigenous population and all sorts of northern and southern European immigrants. It is a tricky identity, that of Latin Americans. I came to the UK for a master’s degree at the RCA in 2015 and we decided to stay. I suppose we were craving for a stable land and a richer country? (Although after 8 years here I have to say I infinitely miss Latin American affections). I honestly cannot remember a time when I didn’t have a pencil and paper or a photographic camera with me. I have been drawing or shooting photography my whole life. I have a constant need to frame thoughts and ideas.

As you’ve told us, your background in architecture has undeniably influenced your work. This is met by a key fascination with music. We’re curious how you see those realms shaping and shifting in your work.

It is quite interesting. I always regretted dropping out of architecture school, always, always. And you know I was a bit unlucky because I would have probably not left if it weren’t because the tutors were not the right fit for me. It was a very male and heteronormative space. There was a lack of interdisciplinary references in our design studio practice and a lot of male-driven tension around. So I think I stuck to the one thing I could control, and that was “an idea of” architecture, or an idea of a space or a feeling of a space. Music has always moved me deeply, I can easily cry or feel rushes of blood in my heart if I listen to either someone playing the cello or a Soundgarden song. I have a special feeling for grunge music produced in the ’90s, but nowadays I am keener on the mega basic lyrics produced in Reggaeton. I suppose it connects me to the anti-sublime, the very evident and sensorial Latin American ways of expressing things.

Could you talk us through your process – how does a drawing begin, what kicks it off? Is it a line, a shape, or perhaps a word? How does the whole pattern unfold?

I love composing spaces, framing spaces, lighting spaces… I think my drawings definitely come as a response to finding control and balance, to keep things in place. I had to survive a very unstable country where we had terrorism, a non-present State, a father who was financially broke, and a very violent and unstable marriage (my parents’). Therefore, my behaviours were shaped by a fight-or-flight environment. I have a lot of noise inside. If you speak to me you realise my thoughts go from A to Z quite easily, I change subjects, I ask a lot of questions, I am too empathetic, and a lot of the classical PTSD you get from childhood trauma. I think the drawings contain me. Not only the performance of the lines is therapeutic, but the frame of the square, the hidden words, the intimacy.

Right now you’re working on your solo show opening in March in London and you’re in the middle of completing new works for it. Seeing the complexity and time-consuming process of the drawings – how do you negotiate time, as it grows shorter till the moment when they must go? But most importantly, we’re struck by how the works, humorously, make visible the dynamics between the structure of the drawings and your own “internal” time, unexpectedly interrupted and animated by “maternal” time, as you’re a mother of two.

One of my biggest challenges is making the drawings mobile, by folding them, cutting them into pieces and taping them back together. Or just making them small. I always try to make my pieces out of cuts of drawings that fit in an A4 folder so I am able to carry them around trains, planes and general travels. Basically that is what I have been doing since my eldest was born, always adapting studio time on the go: I work everywhere. But yes, it is interesting to see how that internal time is constantly interrupted by my writings on them. There are always reflections on domestic errands, you see shopping lists, bills to pay, medical prescriptions, diagnoses, etc. My eldest boy suffers from epilepsy and there is a whole written question in one of the drawings in which I was struggling to figure out what he had. Sometimes, I don’t want to read back what I wrote. The drawings always end up at home on my dining room table, which is the only bright room and the only rectangular table I have at the moment. So the children always end up interfering, either by invading my thoughts and to-do lists or by physically sneaking some line or signature in the paper itself.

Your upcoming exhibition is accompanied by the launch of ‘Draughtswoman’, a book designed in collaboration with Peru-based design studio Estudio Blanco. What’s behind the urgency of making this book right now? How did this collaboration come about?

The idea came up after having a chat with a friend of mine who was a fellow at the British Museum and curated the show about Peru in 2023, her name is Cecilia Pardo. She recently suggested I should put together some writing in relation to my work. We reflected on the fact that writing helps artists get interesting perspectives about their own work, it gives a different weight to the work and it creates a sort of closure. I am also inspired by the mere existence of places like Shreeji, that feel like a mix of different personalities, combining casual coffee with an art exhibition or even a book launch. I have known Estudio Blanco since it started and I knew they were going to solve this in a split second. They are extremely versatile and have an impeccable sensitivity for just anything. Pamela Remy, the owner of the studio, is also a friend and collector of my work. Her husband, Aldo Rodriguez has been making music with my husband for a long time. So there are some sorts of intimacy codes that we share and the communication between us is really easy.

Macarena Rojas Osterling was born in 1985 in Lima, Peru. She studied Architecture at the Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas and subsequently transferred to the Communications Department, where she graduated in 2009. In 2012 she did the General Studies in Photography Program at the International Center of Photography in New York and in 2017 she received her Masters in Fine Arts at The Royal College of Art in London. Her work has been exhibited in Black Box Projects London (2022) Crisis Galería Lima (2019), Art Lima (2018), Museo AMANO Lima (2018), Camden Arts Center London (2017), Edinburgh College of Art (2016), Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Lima (2016), ArtBo Bogotá (2016), Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Santiago de Chile (2014), Wu Galería (2014-2015), International Center of Photography New York (2012), Triskelion Arts New York (2013), amongst other public and privately held exhibitions.